A* SEARCH

Project Overview and Links

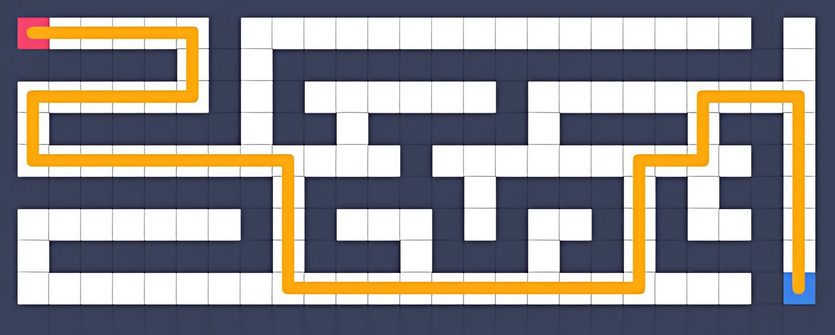

This project is an interactive maze solver. It uses the A* search

algorithm to find the shortest path every time.

To view the full project, click

here 🔗

You can add or erase walls, change the positions of the

start

and end nodes, or randomly generate a maze,

then press space to watch it being solved!

To view the full source code for this project, please click

here 🔗

Introduction & Inspiration

Mazes are fun. School children opening their workbook to solve their homework only to find a page with a maze on it would certainly agree. As we grow up, we may lose the joy of solving a maze, or indeed any other puzzle, turning our attention to more serious problems instead. But in computer science, we regain the appreciation for a good puzzle that adult life might not allow for. Our puzzle today is this: how can we make our computers solve mazes? Or in general, how can we make them solve search problems?

What is a search problem?

A search problem is one where we start at some state S, and keep moving from one state to another until we find our goal state G. Finding the shortest path in the city, looking for the best Scrabble word, and looking for your lost keys at home are all examples of search problems.

Some Search Ideas

The most straightforward approach to the search problem is to exhaust all possibilities. This is what we do when we look for Scrabble words in the middle of a game. We try all words that our letters can create and choose the one which gives the most points. This makes sense when playing Scrabble, because there are only so many words we can make given a set of letters and a game state. But it doesn't make sense when looking for your keys. Why would they be in the fridge? We can restrict ourselves to only looking in places that we suspect our keys might be hiding. But despite using our common sense to avoid looking in unnecessary places, we are still looking blindly among the places we suspect. Let's think about our last problem, finding the shortest path in a city. You might know that your office is up north from where you live. Would you go south looking for a shortcut? It might very well be that there is a magical shortcut which first goes further away from your work and then takes you straight there, but it doesn't seem very likely. Here, we are using a heuristic, a measure of how close we are to attaining our goal. If you are 500m away from work, and you go south, suddenly you are 600m away from work. We don't want that, or at least we don't think we do. Instead, we search for shortcuts in the general direction of our goal. If we don't find any, then sure, we can go look south. If we still don't find any, we can use that as an excuse to be late for work.

A* Search

The idea described in the example above is precisely the algorithm we will be implementing. It's called A* Search, and it was created by a group of scientists at Stanford while building a robot that could plan its own actions. At each step, we look for paths that we haven't explored yet. We calculate the heuristic (which is our measure of how close we are), and the cost (our measure of how much it took us to get here). We add those two measures and choose the path with the least result. If we reach our goal, we can guarantee that we have found the best (shortest) path. If we look at all paths and we don't find our goal, we can conclude that there is no solution.

The Implementation

I'm going to be implementing A* search with the purpose of solving a

maze. Let's start by making a Node class, which will hold the spaces of

our grid. Each node can either be empty or a wall. Each node has "x" and

"y" attributes for its position in the grid. Each node also has a "g"

attribute containing the cost of reaching the node from the start, an

"h" attribute containing the measure of how close we are to the goal,

and an "f" attribute which is the node's total cost. We will also keep a

"previous" attribute to remember how we got from one node to the next,

in order to reconstruct the path we took.

In the real implementation of the algorithm, I have a lot of code

dedicated to drawing the maze, the paths, and adding text and buttons

and keyboard functionality. I will not be explaining this part of the

code below, as it takes away from the algorithm itself.

class Node {

constructor(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.f = 0;

this.g = 0;

this.h = 0;

this.previous = null;

this.wall = false;

}

}

We define openSet and closedSet, containing nodes that need to be evaluated and those that we have finished evaluating, respectively. At the beginning, the openSet contains only the starting node, and the closedSet is empty. The algorithm begins by repeatedly selecting the node from the openSet with the smallest f value.

let openSet = [startNode];

let closedSet = [];

let bestIndex = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < openSet.length; i++) {

if (openSet[i].f < openSet[bestIndex].f) {

bestIndex = i;

}

}

let currentNode = openSet[bestIndex];

We then check if the current node is the goal node. If it is, the algorithm stops, and the path is reconstructed using the "previous" attributes from earlier. We can find our final path length easily:

if (currentNode == endNode) {

let temp = currentNode;

pathLength;

while (temp.previous) {

temp = temp.previous;

pathLength++;

}

}

The algorithm then explores the current node's neighbours, skipping those that are walls. For each neighbour, we calculate the possible g cost. If the neighbour is not in the openSet, or the new "g" cost is lower, update its "g", "h", and "f" values and set its previous to the current node, because we want to go there. Our heuristic function is the Euclidean distance between our current position and the end position.

let tentativeG = currentNode.g + 1;

if (!openSet.includes(neighbor)) {

neighbor.g = tentativeG;

neighbor.h = dist(neighbor.x, neighbor.y, endNode.x, endNode.y);

neighbor.f = neighbor.g + neighbor.h;

neighbor.previous = currentNode;

openSet.push(neighbor);

} else if (tentativeG < neighbor.g) {

neighbor.g = tentativeG;

neighbor.f = neighbor.g + neighbor.h;

neighbor.previous = currentNode;

}

After processing a node, we remove it from the openSet and add it to the closedSet.

removeNode(openSet, currentNode);

closedSet.push(currentNode);

If the openSet is empty and we have not found our end node yet, then there is no solution.

Please use the links above to try it out for yourself!