GENETIC ALGORITHMS

Project Overview and Links

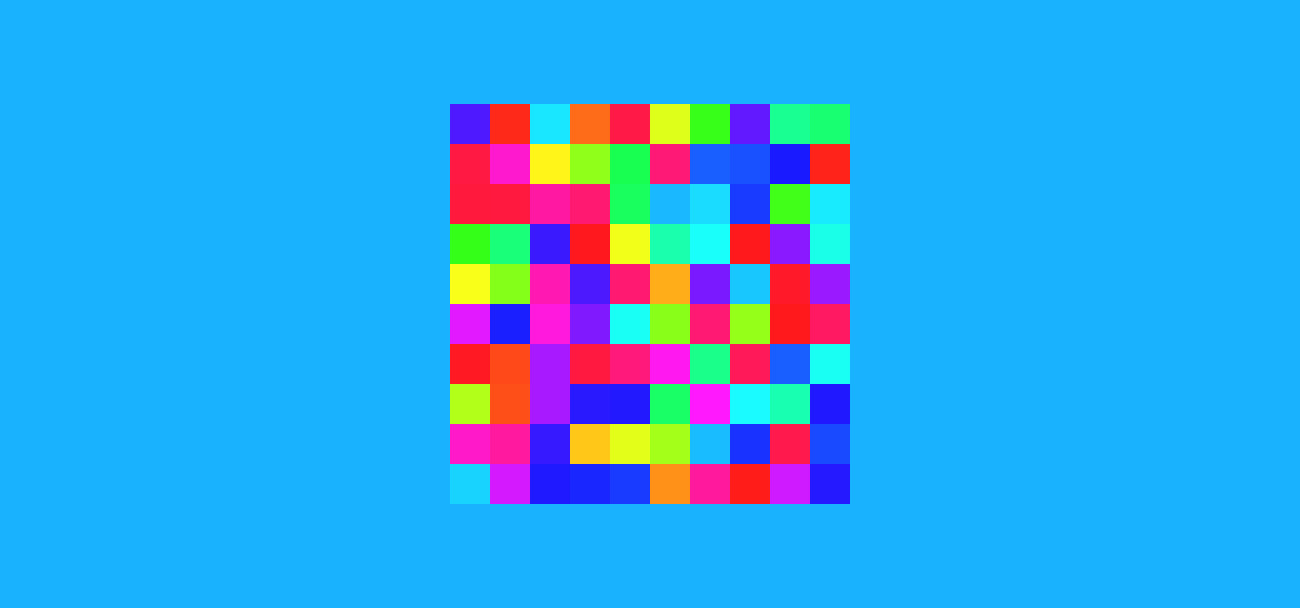

This is an interactive project where you can watch squares change

their color to match a background color using the laws of evolution,

similar to how some animals adapt to their environment in order to

camoflague (see Introduction and Inspiration below).

To visit the project and try it out, please click

here 🔗

To view the full source code for this project, please click

here 🔗

Introduction & Inspiration

I learned this while reading Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder. In Britain, there is a species of butterflies known as peppered moths. They originally had a silver color, because they lived on silver birch trees and it camouflaged them from predators. But due to the industrial revolution, the trees became blackened and the moths underwent a directional evolution in color in order to adapt. They went from being primarily silver to primarily black in some areas. In fact, the black peppered moth was first recorded in Manchester in 1848 and by 1895, 98% of the population in the city was black. I aim to simulate this effect in this project, but with a wider range of colors.

What are genetic algorithms?

Genetic algorithms are optimization techniques inspired by the principles of natural selection. They are used to find the best solutions to complex problems by evolving a population of candidate solutions over time. In this project, I implement the canonical genetic algorithm introduced formally by John H. Holland in his pioneering work, “Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems.” I visualize the algorithm by using it to solve the problem of creatures (squares) adapting to the change in the background color in order to camouflage themselves.

The Steps

Every genetic algorithm, regardless of its specific goal, follows these

steps:

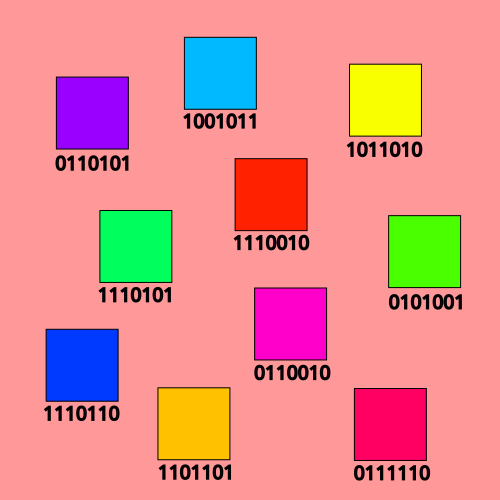

1. Generation: we begin by generating a random

population of "individuals," which are encoded binary strings. We will

assign to each binary string a value depending on the problem we are

solving.

In our case, each binary string will encode a hue value between 0 and

360.

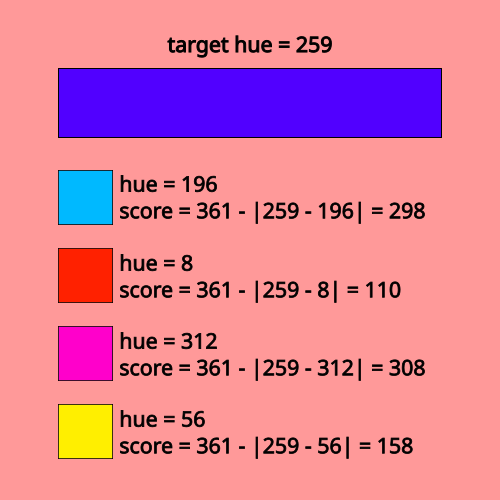

2. Fitness calculation: we calculate the "fitness" of

each individual, which is a number that specifies how close they are to

their goal.

I use the fitness function 361 - |target - value| since it's never 0 on

the interval [0, 360] and it gets higher as our value approaches the

target, as we should expect from a function which measures fitness.

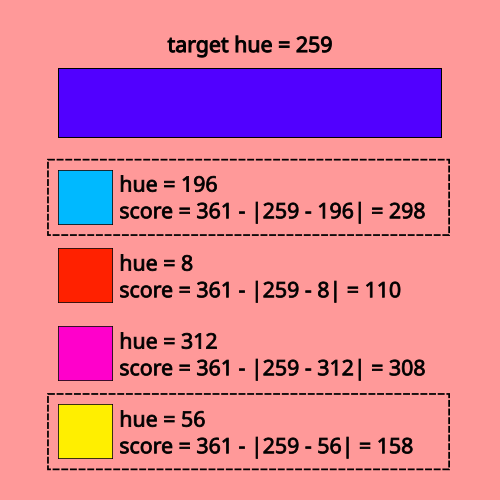

3. Selection: we select the best individuals, which are

those with the highest fitness score. There are two main selection

methods, roulette and truncation. In roulette selection, each fitness

score becomes the probability of the individual being selected for the

next stage. In truncation selection, we choose the top 50% of the

population.

In this project, I have found that truncation selection performs better,

and so it is the chosen method.

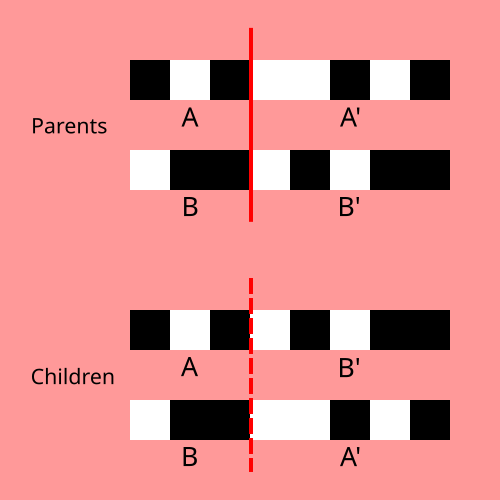

4. Crossover: in the previous stage, we selected our top individuals. They form what we will call a mating pool. We mimic biological reproduction by taking the genes (binary strings) of each two individuals and crossing them with each other, creating the next generation.

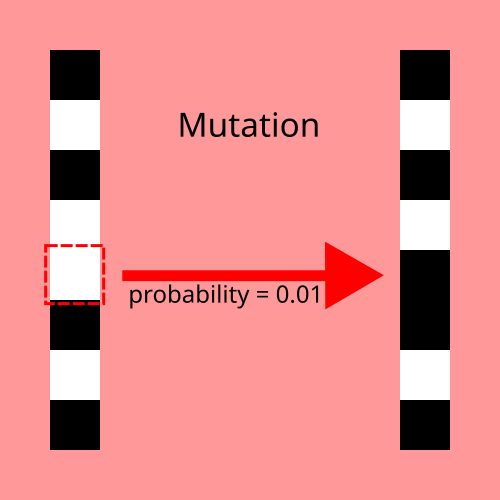

5. Mutation: after we crossover, we apply genetic mutation. This amounts to taking each individual's binary string and changing a 0 to a 1, or the opposite, at a random location based on a very small probability.

6. Repeat: we repeat from step 2, applying the same transformations to our new generation of individuals. With each step, we become closer and closer to an optimized result.

The Implementation

Let's start by creating some utility functions that convert from binary to decimal, and from binary to a value in a given range:

function binaryToDecimal(binaryCode) {

let l = binaryCode.length;

let decimal = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < l; i++) {

let d = int(binaryCode[l - i - 1]);

d *= pow(2, i);

decimal += d;

}

return decimal;

}

function binaryToValue(binaryCode, xMin, xMax) {

let l = binaryCode.length;

let decimal = binaryToDecimal(binaryCode);

let x = xMin + ((xMax - xMin) / (pow(2, l) - 1)) * decimal;

return x;

}

We start by generating a population of individuals, which is a list of binary strings of a given length. The higher the length, the more precise the results are. The reason for this is as follows: if you had to model the numbers between 0 and 360 using binary encoding with length 2, you would only have 4 strings: 00, 01, 10, and 11. So we are forced to assign 00 to 0, 01 to 120, 10 to 240, and 11 to 360. We then miss out on so many numbers in between, and the result can never approach the correct answer in most cases.

function generatePopulation(populationSize, length) {

let population = [];

for (let i = 0; i < populationSize; i++) {

let temp = [];

for (let j = 0; j < length; j++) {

if (random(1) < 0.5) {

temp.push("0");

} else {

temp.push("1");

}

}

population.push(temp.join(""));

}

return population;

}

We want to calculate the fitness of each individual. In practice, this is the function we are optimizing, and it is unique to each problem. We just have to make sure the function behaves as expected, meaning it is higher for values closer to our goal. For some selection methods, we also have to ensure that the function is never 0 on the interval, but it shouldn't matter for ours.

function fitness(binaryCode) {

let value = binaryToValue(binaryCode, 0, 360);

return 361 - abs(targetHue - value);

}

We calculate the fitness of each individual and sort our population by score.

function populationFitness(population) {

return population.map((individual) => ({

i: individual,

f: fitness(individual),

}));

}

function sortByFitness(populationFitness) {

return populationFitness.sort((a, b) => b.f - a.f);

}

We need to select the top 50% of individuals in order to use them in the mating pool.

function top50Percent(populationFitness) {

let sorted = sortByFitness(populationFitness);

let size = Math.floor(sorted.length / 2);

return sorted.slice(0, size).map((individual) => individual.i);

}

Now that we have a mating pool, we need to create the next generation of individuals by simulating reproduction. We do this as follows: first, choose two random individuals, the parents, from the mating pool. Next, pick a random position along the binary string. We then swap the genes (the binary bits) of the two parents around the random position, creating two new individuals, the children.

function crossover(matingPool) {

const result = [];

while (matingPool.length >= 2) {

const index1 = floor(random(matingPool.length));

let index2 = floor(random(matingPool.length));

while (index1 === index2) {

index2 = floor(random(matingPool.length));

}

const parent1Index = max(index1, index2);

const parent2Index = min(index1, index2);

const parent1 = matingPool[parent1Index];

const parent2 = matingPool[parent2Index];

const position = floor(random(parent1.length));

const child1 = parent1.slice(0, position) + parent2.slice(position);

const child2 = parent2.slice(0, position) + parent1.slice(position);

result.push(child1);

result.push(child2);

matingPool.splice(parent1Index, 1);

matingPool.splice(parent2Index, 1);

}

return result;

}

But we need more randomness if we were to simulate biological evolution. We will introduce mutations, which are the random inversion of bits in the genes of individuals. Without this step, two parents with the same genes will always produce the same children, and evolution never occurs.

function mutate(crossover) {

return crossover.map((individual) => {

let ind = [];

for (let i = 0; i < individual.length; i++) {

if (random(1) < mutation_rate) {

ind.push(individual[i] === "0" ? "1" : "0");

} else {

ind.push(individual[i]);

}

}

return ind.join("");

});

}

Finally, we combine all those functions into one function that generates the next generation of individuals given the current population.

function nextGeneration(population) {

let popFitness = populationFitness(population);

let topIndividuals = top50Percent(popFitness);

let matingPool = [];

for (let i = 0; i < topIndividuals.length; i++) {

matingPool[i] = topIndividuals[i];

}

let offspring = crossover(matingPool);

let offspring2 = mutate(offspring);

let newPopulation = topIndividuals.concat(offspring2);

return shuffle(newPopulation);

}

Visualization

In order to visualize this process and make it interesting, I am using a library called p5js which makes drawing for the web easy, straightforward, and fun. I am convering the genes of each individual into a hue value and drawing a square in the corresponding color to simulate the creatues adapting to the background.

function drawGrid(population) {

let cols = floor(sqrt(populationSize));

let rows = cols;

let size = squareWidth / cols;

let k = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < cols; i++) {

for (let j = 0; j < rows; j++) {

noStroke();

fill(binaryToValue(population[k], 0, 360), 90, 100);

let x = i * size + (width - squareWidth) / 2;

let y = j * size + (height - squareHeight) / 2;

square(x, y, size);

k++;

}

}

}

We get our final result, a population of creatures adapting to their background without being explicitly programmed!

The canonical genetic algorithm with truncation selection described here

is easy to implement and yet offers great insight into biological

evolution and optimization problems. Being inspired by nature and its

laws is the primary source of creativity and its application to

problem-solving.

Please play around with the full project using the links above! You can

change the background color and rate of mutation using sliders and watch

the creatures adapt!